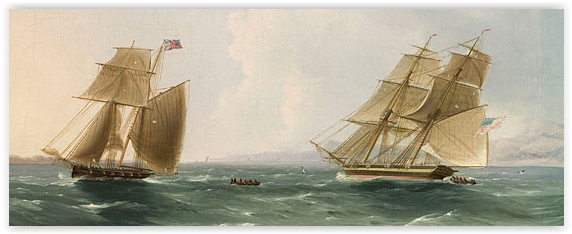

U.S. privateer Warrior capturing British merchant ship Hope. Detail of a painting by Thomas Birch. Smithsonian Institution I.D. #2005.0279.021

In a recent posting I noted the story of a French privateer which had captured a vessel from P.E.I. and the details suggested a measure of “fair play” in the conduct of the French commander. That was not always the case and when the Americans joined the fray the actions became more heated. During the three years of the war the American privateers may have captured as many as 2000 British vessels, almost ten times the number captured by the U.S. Navy! The privateers sank or stole one in every fifteen merchant vessels in the British merchant marine.

The targets were not just heavily laden vessels with valuable cargos. At the time of the timber boom many ships came out to Prince Edward Island and other timber ports carrying emigrants to the new land but more often they were in ballast – empty ships hoping to come back with valuable masts, deals, square timber and lathwood crammed into their holds and on deck. One such vessel was the ship Royal Bounty which came out from the Scots port of Leith in the summer of 1812. The ship had spent much of its life as a whaling ship exploiting the rich Davis Strait off the west coast of Greenland although in 1811 it had carried at least one cargo of timber from Quebec to Leith. Whaling ships were stoutly built and had a larger carrying capacity than ordinary merchant vessels. Earlier in that year it had been advertised for sale after some repairs and the sale notice stated “The ship stows an uncommonly large cargo for her tonnage, and would suit well for a Greenlandman, or Mast Ship.”

Caledonian Mercury 26 January 1811 p.1

She was so well suited as a “Mast Ship” that at the beginning of August 1812 she found herself just off the south coast of Newfoundland heading for Prince Edward Island to be loaded with timber. She never arrived. Instead, she became one of the first vessels captured by privateers in a war which had broken out after her departure and of which the captain and crew were unaware.

CAPTURE OF THE ROYAL BOUNTY OF LEITH

St. John’s Aug 13

On Monday evening last arrived here, Capt. Henry Gamble, with part of his crew and passengers, belonging to the the Royal Bounty of Leith. This vessel on her voyage from Hull to Prince Edward’s Island, in ballast, was attacked on the 1st instant, four or five leagues to the southward of St. Peters,[most likely the island of St. Pierre, off the Burin Peninsula] by the Yankee, brigantine privateer, of 18 guns and 120 men.

Captain Gamble, being unapprised of the war, was in some degree unprepared fo the attack of the Americans, who chased him under English colours, but, on coming near, hoisted the American flag, and commenced the engagement.

The Royal Bounty had 10 guns, 18 men, and four passengers — one a female. Captain G. sustained the unequal conflict for an hour and a quarter, when having the boy that was on the helm killed, himself wounded, together with his second mate, boatswain, and cook, the colours were struck; several shots were fired afterwards, one of which wounded the chief mate. The Americans then took possession, and ordered all the people on board the privateer, where the wounded received surgical assistance, but the others were treated very harshly, having their clothes, some of which they wore, taken from them.

Two Americans were badly wounded, and it is supposed some were killed, but this was not acknowledged. The American master was quite enraged at the resistance he had met with from Captain Gamble, whose conduct on this occasion, as well as his gallant associates, deserves the approbation of every brave man.

The privateer, shortly after, boarded the Thetis, of Poole, Captain Pack from Sydney, with coals, which was set fire to, as well as the Royal Bounty. The crew of the former escaped. At 11 at night, Captain Gamble, with his crew were set adrift in the boat. They reached the land of Placentia Bay the next morning — after receiving the most hospitable treatment at Lamallin, [Lamaline is at the southern tip of Newfoundland’s Burin Peninsula] they were conveyed from thence to Burin …..

The privateer, we are led to believe, has done a good deal of mischief on the south-west coast, but we hope Captain Cooksesley of the Hazard, who must have been near that part of the coast, will put a stop to his career.

Caledonian Mercury 19 September 1812 p.3

In spite of the hopes of the newspaper His Majesty’s sloop-of-war, HMS Hazard which was indeed on the Newfoundland station in 1812 never did encounter the Yankee as the warship had been sent back to England before the Royal Bounty left Leith. The Royal Bounty had been particularly unlucky. The Yankee was to go on to be the most successful American privateer of the short war, sinking or capturing more than five million dollars of British property and pumping more than a million dollars of profit into the economy of her home port of Bristol Rhode Island. Details of her six cruises with more than twenty prize vessels to her credit can be found in an American Antiquarian Society article published in 1913 and found here. The article provides interesting details of the articles of agreement between the owners and crew including the split of the profits and a kind of insurance so that anyone who lost an eye or a joint would get fifty dollars, for loss of a leg or arm the payment would be three hundred dollars – but only if the voyage was profitable!

To the Yankee the Royal Bounty was of little value. Instead of a rich cargo its hold was empty and the dispatch of crew to sail it back to Bristol would weaken the fighting strength of the privateer. Even getting the Royal Bounty back to an American port was a problem as it was not uncommon for prizes to be re-captured and in some cases re-re-captured. Small wonder then that the ship was burnt and the crew put over the side in a crowded ship’s boat to find their way to the barren coast of Newfoundland in the dark.